ADHD women and eating: practical strategies to rebuild a healthier relationship with food

Table of Contents

-

Introduction: ADHD, women and food – what’s really going on?

-

Conclusion: You’re not “lazy” – your brain is wired differently

Introduction: ADHD, women and food – what’s really going on?

If you are a woman with ADHD, eating can feel chaotic. One day you forget lunch completely; the next you inhale half a packet of biscuits before you notice you are eating. Many clients at AusClin say, “I know what I should eat. I just cannot seem to do it.” That is exactly where ADHD and eating intersect.

ADHD affects how you plan meals, sense hunger and fullness, manage emotions, and make snap decisions around food. Impulsivity, inattention, hyperfocus, and emotional intensity can lead to unconscious snacking, skipping meals, craving convenient fast food, and using food as an emotional pressure valve. These links between ADHD traits and disordered eating behaviours are highlighted in reviews of ADHD and disordered eating.

This article outlines why these patterns are so common in women with ADHD, how they raise the risk of disordered eating, and ADHD-friendly strategies from AusClin to bring more structure and ease into your eating without strict rules or guilt.

How ADHD shapes everyday eating patterns in women

Many women with ADHD describe eating as “all-or-nothing”. You might graze all evening while scrolling your phone, then barely eat during a busy workday. This reflects ADHD traits rather than willpower. Impulsivity and inattention make it easy to eat on autopilot, especially when you are watching TV, working, or on social media. Research shows that women with ADHD often snack unconsciously while engaged in other activities, with little awareness of how much they have eaten.

Convenient options like fast food, takeaway, and packaged snacks tend to win because they require fewer steps, less planning, and no waiting time. When executive function – the brain’s planning and organisation system – is overloaded, cooking from scratch can feel like climbing a hill in wet sand, a pattern described in work on how ADHD influences eating patterns. In this context, relying on “willpower” usually falls short. An ADHD brain seeks quick rewards and low barriers. If the pantry is full of chips and lollies and there is no prepared food, the choice is almost made before you open the cupboard.

Building an environment that supports easier decisions – for example, ready-to-eat, nourishing options at eye level – is often more effective than trying to “be disciplined”. A specialised clinic like AusClin can help tailor your food environment and routines so they work with your brain’s wiring.

Between work, caring roles, study, and household duties, meals are often squeezed into gaps. When you are mentally overloaded, it is natural to reach for whatever is simplest, even if it does not leave you satisfied. Many women recognise themselves in real-life stories shared on ADHD in women and eating habits. Understanding that these patterns are brain-based, not moral failings, is often the first step toward change.

Emotional eating and ADHD in women

Emotional regulation is a major challenge for many women with ADHD. Feelings can arrive fast and intensely: stress, boredom, frustration, loneliness, or the crash after hyperfocus. Food, especially high energy options, offers quick relief.

Many women with ADHD use food to cope with emotional surges. You might wander to the fridge when a work email upsets you, or find yourself baking late at night after a draining day. High energy options deliver a short-term hit of comfort or distraction, which your brain remembers. Over time, this builds a loop: strong emotion → eat → brief relief → guilt or shame → more emotion.

ADHD can also make it harder to pause and notice what you are feeling. Instead of identifying “I am anxious”, your body might just feel restless, and you respond automatically with food. This is one reason emotional eating can feel like it happens “to” you rather than being a conscious decision.

Working with an expert clinical dietitian who understands ADHD means support goes beyond food choices to emotional coping. That might include grounding exercises before you open the pantry, “pause” rituals like having a glass of water and naming your feeling out loud, or planning non-food comforts that are ready to go: a warm shower, a favourite show, a walk, or calling a supportive friend. Dietitians at services like AusClin often collaborate with psychologists so your emotional and nutrition care align.

Hyperfocus, forgetfulness and irregular meals

Another common pattern in ADHD women and eating is irregular or skipped meals. Hyperfocus – the intense concentration many people with ADHD experience – can be both a strength and a trap. When you fall into a deep work project, game, craft activity, or cleaning spree, hours can disappear and meals simply vanish from your awareness.

General forgetfulness plays a role too. You might buy ingredients for a healthy lunch, then leave them untouched because you forget they exist or feel overwhelmed by the steps needed. By the time you notice hunger, you are often ravenous, irritable, and exhausted. In that state, your brain is wired to reach for the fastest calories, usually ultra-processed foods rather than balanced meals.

Over time, this irregular eating can contribute to fatigue, mood swings, headaches, and nutrient gaps. Iron, B vitamins, and protein can all fall short when meals are sporadic, especially if breakfast and lunch are often skipped. Women already have additional nutrient demands due to menstrual cycles, pregnancy, and perimenopause, so chaotic eating can have a noticeable impact. Addressing these gaps is a key focus of fertility and preconception nutrition support and pregnancy and postpartum care at specialised clinics.

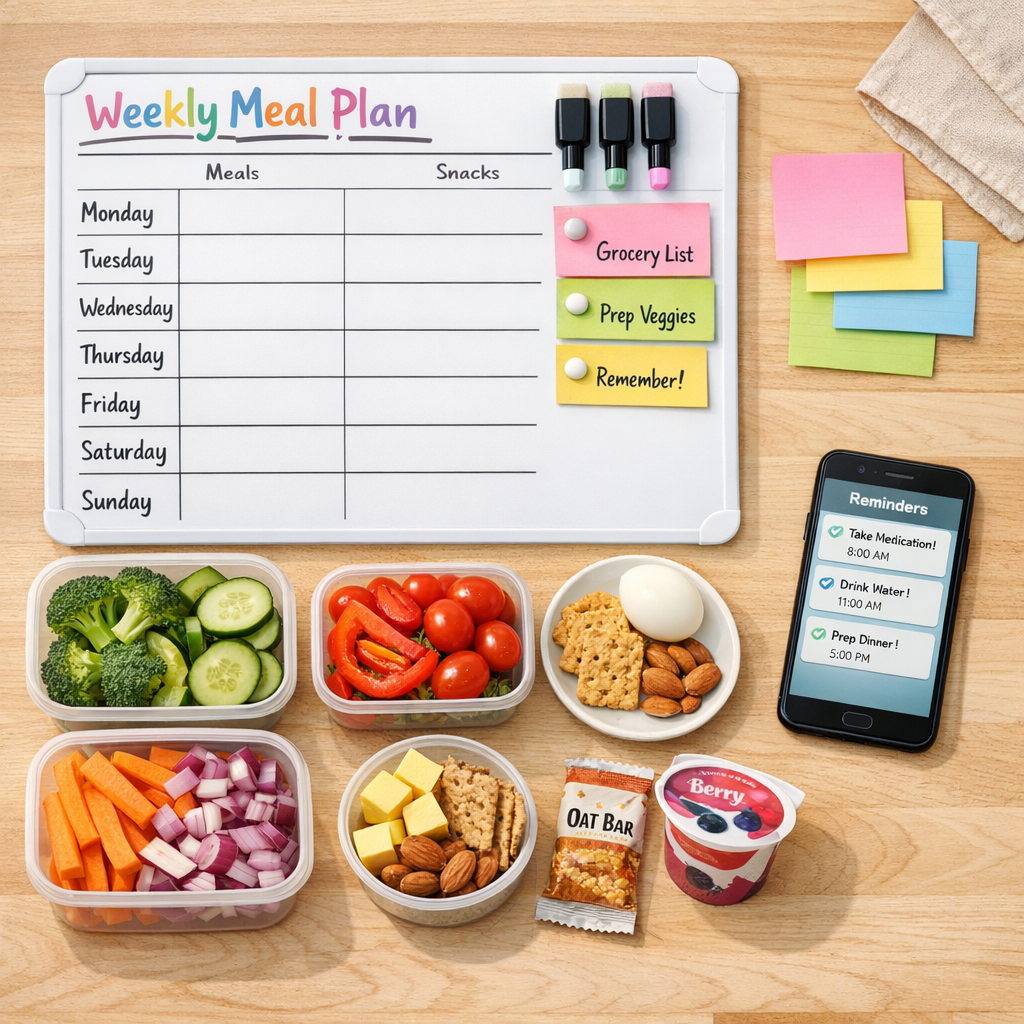

One effective way to counter this is to externalise your memory. Instead of relying on your brain to remember to eat, you build prompts and structure around you: phone alarms labelled “eat something, even if small”, visual cues such as a fruit bowl on your desk, or pre-assembled snacks visible in the fridge. A planned framework does not have to be rigid; too much rigidity usually backfires for an ADHD brain. The goal is regularity, not perfection.

ADHD and eating disorders: understanding the higher risk

ADHD is strongly linked with a higher risk of eating disorders. Studies show that people with ADHD are nearly four times more likely to develop an eating disorder than peers without ADHD. The overlap is especially strong with binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa, which involve impulsive or loss-of-control eating episodes. There is a weaker, but still present, association with anorexia nervosa, a pattern echoed in summaries from organisations such as the National Eating Disorders Association.

Several ADHD traits line up with known risk factors for eating disorders. Impulsivity can drive rapid eating and difficulty stopping once you start. Emotional dysregulation can fuel cycles of comfort eating followed by intense guilt. Inattention can make it harder to notice hunger and fullness cues. Perfectionism (which many women with ADHD quietly carry) can contribute to rigid dieting or “all-or-nothing” food rules.

Many women with ADHD also have a history of feeling “too much” or “not enough” – too loud, too messy, too distracted, too disorganised. Controlling food or body size can feel like a way to finally be “good enough”, even though it usually leads to more distress. When these pressures sit alongside impulsive, chaotic eating, the risk of sliding into disorders like binge eating or bulimia rises sharply, a connection also discussed in clinical commentaries on ADHD and disordered eating.

If any of this soun

Structured meal planning strategies that work with ADHD

Traditional meal planning advice often fails women with ADHD because it assumes a steady schedule, consistent energy, and strong executive functioning. Long recipes, detailed shopping lists, and strict weekly menus usually fall apart by midweek. Instead, you need structure that is flexible, forgiving, and easy to restart when life gets messy. ADHD-informed meal planning focuses on scaffolding rather than perfection, and this is where working with a dietitian service like AusClin can help.

Structured meal planning for ADHD typically includes:

-

Scheduled meal times – broad anchors like “breakfast by 9am”, “lunch around 1–2pm”, and “dinner by 8pm”, backed by phone reminders or calendar alerts.

-

Planning in short blocks – choosing a handful of simple meals for the next 2–3 days rather than a whole week to reduce overwhelm and waste.

-

Stocking key ingredients – keeping a small list of basics that can quickly form a meal: eggs, frozen vegetables, microwave rice, tinned beans or tuna, yoghurt, fruit, and wraps.

-

Batch cooking – preparing larger portions of 1–2 easy recipes when you have energy, then freezing or refrigerating individual serves.

For women with busy or unpredictable schedules, modular “meal blocks” can make a big difference. Instead of rigid recipes, you create interchangeable components such as:

-

Carbohydrate options – rice, pasta, couscous, grainy bread, potatoes.

-

Protein options – chicken, tofu, lentils, eggs, beef strips, Greek yoghurt.

-

Vegetable or salad options – pre-cut salad mixes, frozen stir-fry vegetables, cherry tomatoes, baby spinach.

When it is time to eat, you choose one item from each group. This reduces decision fatigue because the choices are already narrowed, but still gives enough variety to avoid boredom. Many AusClin clients find that once these blocks are set up, the mental load of “what’s for dinner?” drops dramatically.

Batch cooking can be as simple as doubling a basic pasta sauce, baking extra chicken thighs while the oven is on, or cooking a big pot of soup on Sunday for several lunches. The aim is to have “good enough” options available so that, when your brain is tired or distracted, nourishing yourself requires as few steps as possible.

Practical tips to start changing your ADHD eating patterns today

Change happens through small, concrete steps. You do not need to overhaul everything this week; trying to do that is a classic ADHD trap. Instead, pick one or two of these strategies and test them for a week or two, then adjust.

-

Set three food alarms a day. Label them clearly: “Breakfast – fuel your brain”, “Lunch – pause and eat something”, “Dinner – time to refuel”. Even if you only manage a snack at first, you are building the habit of checking in.

-

Create a visible snack station. Stock it with nourishing, low-effort options: nuts, fruit, cheese and crackers, yoghurt pouches, boiled eggs. Put it at eye level in the fridge or pantry so you see it before less helpful foods.

-

Use the “minimum meal” rule. On days when cooking feels impossible, aim for a basic trio: one protein, one carbohydrate, one fruit or vegetable. Beans on toast with cherry tomatoes counts. Scrambled eggs and toast with a piece of fruit counts.

-

Pair food tasks with routines you already have. For example, make overnight oats while you wait for the kettle in the evening, or prep tomorrow’s snack box straight after dinner dishes. Linking habits reduces the need to remember from scratch.

-

Practice one non-food coping strategy for emotions. Choose a simple action like stepping outside for two minutes, slow breathing, or texting a friend. When you feel an emotional urge to eat, try this first, then decide whether you still want food.

If you are not sure where to start, working with a dietitian who understands ADHD can shortcut a lot of trial and error. At AusClin, we tailor these strategies to your life stage, culture, budget, and medical needs, so they are actually doable. The aim is not to control every bite, but to help you feel steadier, more energised, and less at war with your own body.

Conclusion: You are not “lazy” – your brain is wired differently

The patterns many ADHD women experience with eating – unconscious snacking, skipped meals, emotional overeating, swings between restriction and excess – are logical outcomes of an ADHD brain navigating a busy, demanding world. Recognising this does not remove responsibility, but it does remove blame. You are not broken; you need strategies built for the way your mind actually works, ideally through coordinated care that recognises the overlap between PCOS, endometriosis, and ADHD-related eating patterns where relevant.

With flexible structure, practical planning, and new emotional tools, it is possible to build a calmer relationship with food. You deserve meals that leave you satisfied, energy that lasts beyond mid-morning, and a body that feels cared for rather than punished. If you would like tailored support from an expert clinical dietitian team that understands ADHD, reach out to AusClin to book an appointment and start reshaping your eating in a way that feels sustainable.

© 2026 AusClin. All rights reserved.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do so many women with ADHD struggle with eating and food routines?

ADHD affects planning, impulse control, time awareness and emotional regulation, all of which directly impact how you eat. This can look like skipping meals, bingeing in the evening, relying on convenience foods, or using food to cope with big emotions. Hormonal changes across the month can also intensify ADHD symptoms, which in turn can disrupt appetite and cravings. These are brain-based patterns, not a lack of willpower.

How does ADHD actually change my hunger cues and eating patterns?

ADHD can make it harder to notice subtle hunger and fullness cues because your attention is often pulled elsewhere. Many women report going from ‘not hungry’ to ‘starving’ very quickly, then eating fast and past fullness. Hyperfocus can mean you work through meals without realising, while impulsivity can lead to grabbing the quickest, most rewarding food when you finally notice you are hungry. Over time this creates a cycle of irregular meals and big energy crashes.

What is the link between ADHD in women and emotional eating or binge eating?

Women with ADHD are at higher risk of emotional eating because food is an easy, fast way to soothe overwhelm, boredom, shame or rejection sensitivity. Difficulties regulating emotions and stopping once you’ve started can turn comfort eating into binge episodes. Many also carry years of criticism about being ‘messy’ or ‘undisciplined’, which can fuel secretive or guilt-driven eating. Treating ADHD and developing healthier coping tools often reduces emotional and binge eating over time.

How can I manage irregular meals when ADHD makes me forget to eat?

External structure helps more than relying on memory or ‘listening to your body’ alone. Use phone alarms, calendar reminders or smartwatches to cue meals and snacks at roughly consistent times. Keep easy, no-prep options (like yoghurt, cheese and crackers, nuts, pre-cut fruit, frozen meals) visible and ready to grab. Many women also find that pairing meals with existing habits (e.g. coffee + toast, lunch straight after a meeting) makes eating more automatic.

Are women with ADHD more likely to develop an eating disorder?

Research suggests people with ADHD have higher rates of disorders like binge eating disorder, bulimia and some forms of restrictive eating. Traits such as impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, low self-esteem and a history of weight stigma all contribute to this increased risk. For women, late or missed ADHD diagnoses often mean years of unexplained struggles with food and body image. Early assessment and ADHD-informed treatment can reduce the chance that disordered eating becomes an entrenched eating disorder.

What are some realistic meal planning strategies that actually work with ADHD?

Instead of complex weekly plans, use simple, repeatable frameworks like ‘3 breakfasts, 3 lunches, 3 dinners on rotation’. Plan around your actual energy levels and schedule—for example, batch-cook on higher-focus days and rely on shortcuts (frozen veg, pre-cooked proteins, meal kits) on low-capacity days. Visual tools like whiteboards, clear containers and fridge lists reduce decision fatigue. AusClin clinicians often help clients build personalised systems that match their ADHD profile and life demands.

How can I start rebuilding a healthier relationship with food if I have ADHD?

Begin by dropping the shame and reframing your eating patterns as ADHD-related, not personal failure. Focus on adding structure and support—regular meals, satisfying snacks, and environments that make the easier choice the healthier one—rather than strict dieting rules. Work on awareness of triggers (e.g. long gaps without food, certain emotions, specific times of day) and experiment with alternative coping strategies. Many women benefit from working with an ADHD-informed psychologist or dietitian, like those at AusClin, to do this safely and sustainably.

What practical first steps can I take today to feel more in control around food with ADHD?

Aim for just one or two small, doable changes rather than an entire overhaul. Examples include: setting two meal alarms, prepping one snack box for tomorrow, or eating something within an hour of waking. Put some nourishing foods where you can see them (bench, front of fridge) and move highly tempting snack foods out of sight or into harder-to-access spots. If you notice patterns you can’t shift alone—such as frequent binges or extreme restriction—book an assessment with a clinician experienced in ADHD and eating, like the team at AusClin.

How can AusClin help women with ADHD who are struggling with food and eating?

AusClin provides ADHD-informed assessments and therapy that consider how your symptoms interact with eating, body image and daily routines. Clinicians can help you understand your patterns, address emotional eating, and build practical systems for regular, flexible meals that fit your life. Where needed, they work alongside GPs, psychiatrists and dietitians for a coordinated approach. Sessions are available to explore both ADHD treatment options and tailored strategies to rebuild a healthier relationship with food.